Lovers of the Hebrew Stage was the first theater troupe established in the Land of Israel. Founded in Jaffa in the early twentieth century, the group produced works of classical and modern theater in Hebrew. The city’s Orthodox leadership tried to stop the performances. The rabbis were against the use of Hebrew for non-religious purposes; they also opposed women appearing on a stage and the interaction between men and women in the audience. The Lovers of the Hebrew Stage persevered anyway. The beginning of Hebrew theater is an important part of the development of Hebrew culture and the home it eventually found in Tel Aviv.

by Yadin Roman

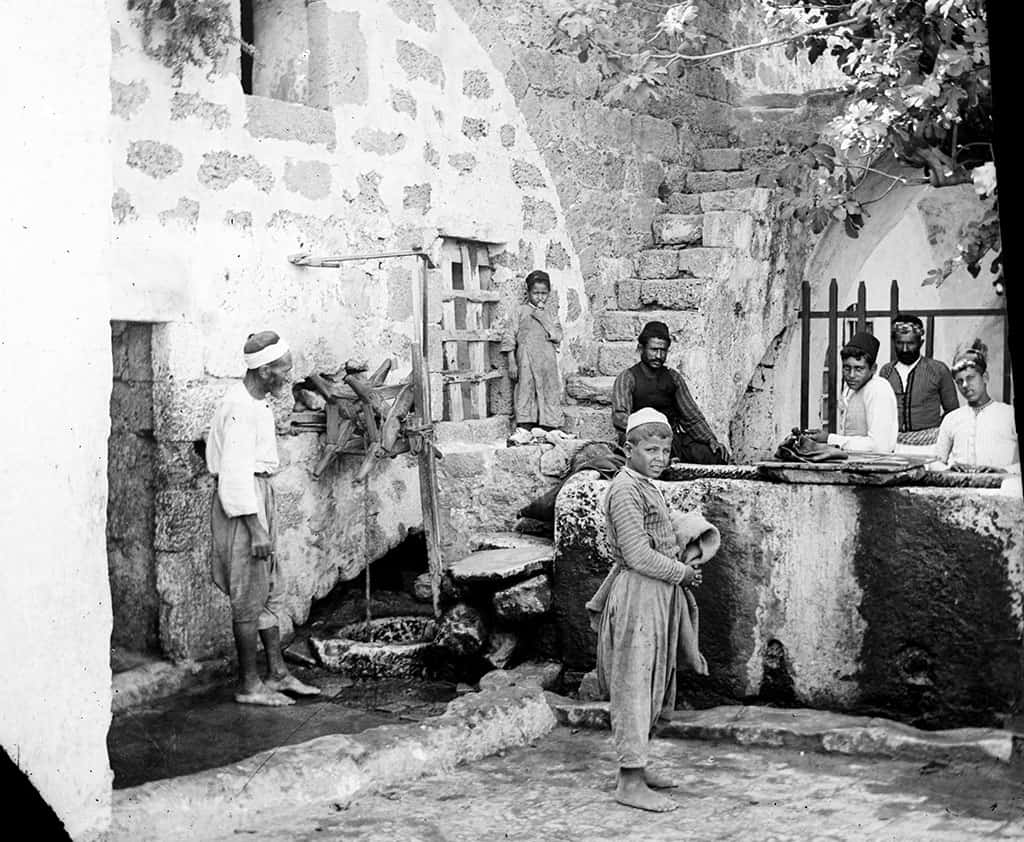

The Jewish community in Jaffa established itself following the first aliyah in the 1880s. Jaffa, the largest town in the Land of Israel and its main port of entry, hummed with young Jewish immigrants as well as youngsters who had been born at the Jewish settlements around Jaffa and migrated to the big city. They spent their time seeking work, which was not abundant, and socializing in the khans and coffee houses that lined the main streets and markets. Here, in Jaffa, the young Jewish laborer could read the Hebrew newspapers and keep abreast of the latest news, job opportunities, and social events.

Hebrew as a living, spoken language developed in the circles affiliated with the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment) movement in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. One popular method of propagating the Haskalah movement’s ideas and developing a national culture was forming theater clubs that produced plays with amateur actors. These troupes soon became the spearhead for advancing Hebrew culture in Jewish centers throughout Europe. In 1904, this concept reached the Land of Israel and the first theater club in Jaffa was founded: the Lovers of the Dramatic Art.

The members of the new theater group were passionate about Hebrew so their first two productions were in Hebrew. The first play, which debuted on Purim 1905, was Uriel Acosta, which tells the story of sixteenth-century Jewish philosopher and skeptic Uriel da Costa. The play was based on the biography of him that German author Karl Gutzkow wrote in 1846. The biography had been turned into a play and translated into Yiddish. The result became a staple of Yiddish theater. The Lovers of the Dramatic Art translated the play into Hebrew and gave their first performance in an Arab coffee house on Bustros Street, Jaffa’s main commercial thoroughfare (today David Raziel Street).

In an article titled, “The First Hebrew Play in the Land of Israel,” the Jerusalem-based Hebrew newspaper Hahashkafa reported: “Jews who had never before stepped into a coffee house came dressed in their finest clothes. They came from the Jewish settlements in carts, women and children sitting in the carts and men walking alongside them, to see the first Hebrew play ever produced in Jaffa. The crowd making its way to Jaffa included Menahem Gnessin, who played the lead role. Gnessin, a laborer at the Rishon Lezion winery, had taken leave for the performance and walked all the way to Jaffa…. Of the artistic value of the play nothing can be said, but the stupendous act of staging a play in Hebrew, which the audience could plainly understand, was the talk of the day.”

A play in Hebrew whose cast included actresses immediately incurred the wrath of the rabbis of the Old Yishuv, especially those in Jerusalem. When the group put on its second play, The Jews by Russian author A. Zerikov, the rabbis went on a rampage. The day the play was scheduled to open in Jerusalem, they sent messengers to all the synagogues in the city to announce that going to see the play was strictly banned. Posters also appeared in the Jewish neighborhoods denouncing the “theater where men and women appear together.”

The play encountered other difficulties, the main one being that a large part of the audience and some of the actors did not speak Hebrew. After a heated debate, the group decided to produce future plays in Yiddish since it was understood by most members of the Old Yishuv and the ultra-Orthodox population as well as immigrants from the first aliyah.

Some members of the group objected to the decision to perform in Yiddish; they withdrew from the Lovers of the Dramatic Art and created a new group, Lovers of the Hebrew Stage, to produce plays that were written in Hebrew or translated into Hebrew.

In 1909, the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage welcomed its first star: a young woman from Alexandria named Lisa Varon, who had appeared a few times with Yiddish theater troupes in Egypt. Even though she did not know Hebrew, the audience loved her acting, her voice, and her beauty.

“As the eyes of all the people are upon us, we cannot look down with disdain on our language and perform in a language that is just jargon,” the members of the new group announced.

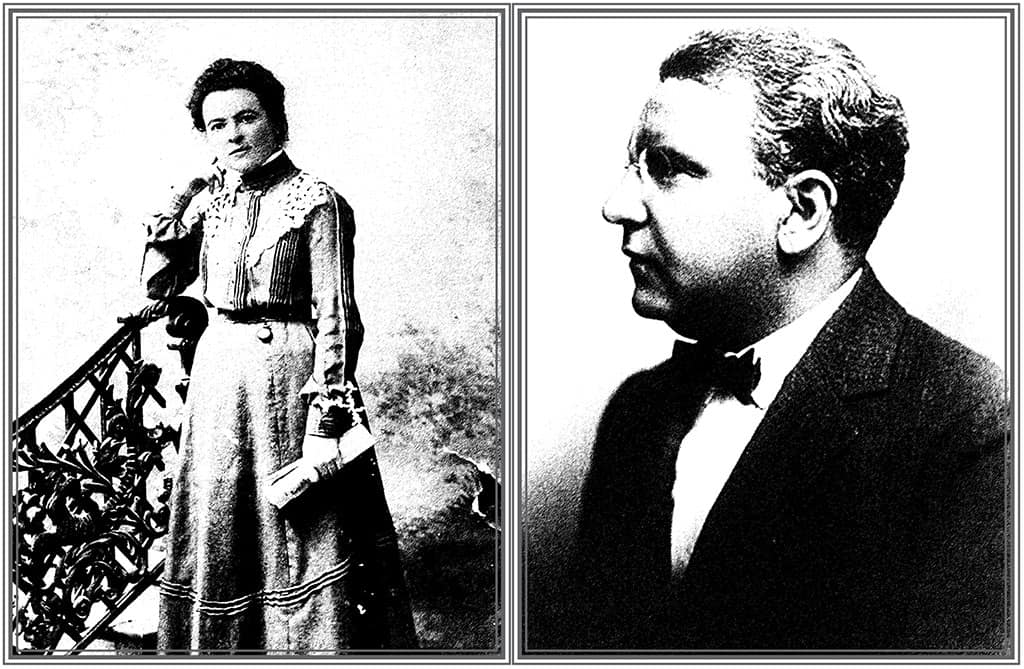

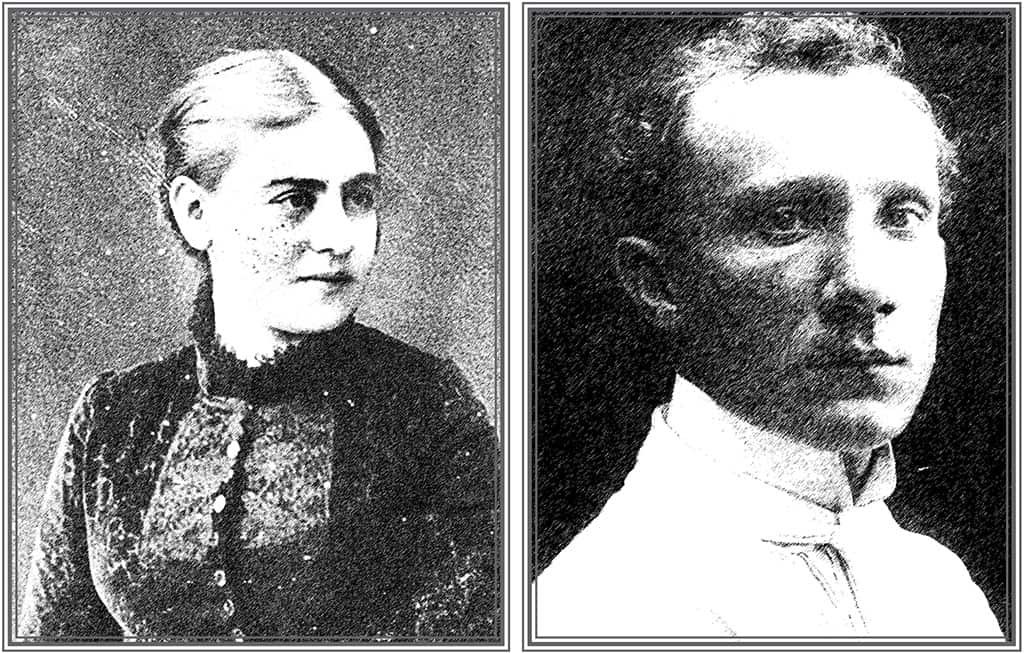

The central figures in the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage were Dr. Hayyim Harari, a teacher and skilled amateur actor, and his wife, Yehudit Eisenberg. They were joined by Gnessin, from the winery in Rishon; Fania and Yehudah Leib Metman-Cohen, founders of the Herzliya Gymnasia in Jaffa; and Olga Hankin, the wife of Yehoshua Hankin, who would go on to buy huge tracts of land for the Jewish Agency.

Harari was born in Latvia. His father Dov Blumberg was one of the founders of the Hovevei Zion movement and instilled him with a love of Hebrew and a yearning for the rebirth of the Jewish nation in its homeland. From a young age, Harari wrote for the Hebrew press, signing his articles with the name of an ancient Talmudic sage, Ben Bg Bg. In 1896, at the age of 13, he made aliyah to study agriculture at the Mikveh Israel School near Jaffa. He joined the school’s drama club and participated in the production of plays in French, the main language used at the school. He graduated five years later, in 1901. Harari’s attempts to settle in Palestine as a farmer were thwarted when the Ottoman authorities enacted new ordinances barring Mikveh Israel’s international students from settling in the country upon graduation. Harari decided to dedicate his life to education and enrolled at the University of Geneva in Switzerland to study education, psychology, literature, and the dramatic arts. There, together with his new classmates, Chaim Weizmann and Zvi Averson, he engaged in promoting Zionism among the Swiss Jewish community.

In 1906, he returned to the Land of Israel and found employment teaching general and Hebrew literature at the Herzliya Gymnasia in Jaffa.

Yehudit Eisenberg, who would marry Harari in 1907, was born in Pinsk, Belarus. Her parents made aliyah in 1866, when she was just a few months old. During their first year in the country, the family lived in Jaffa. Then they bought a plot of land in Wadi Hanin, the future settlement of Ness Ziona. At first, the family lived in a tent among the Bedouins. After a few months, they moved to a cellar in the orchard of Reuven Lerrer, the founder of the Jewish settlement in Wadi Hanin. When the Bedouins told the family that the land of nearby Khirbet Duran was for sale, Eisenberg’s father teamed up with his friend Yehoshua Hankin to buy the land. In 1890, when Eisenberg was five, the family moved to Khirbet Duran, which grew into the town of Rehovot.

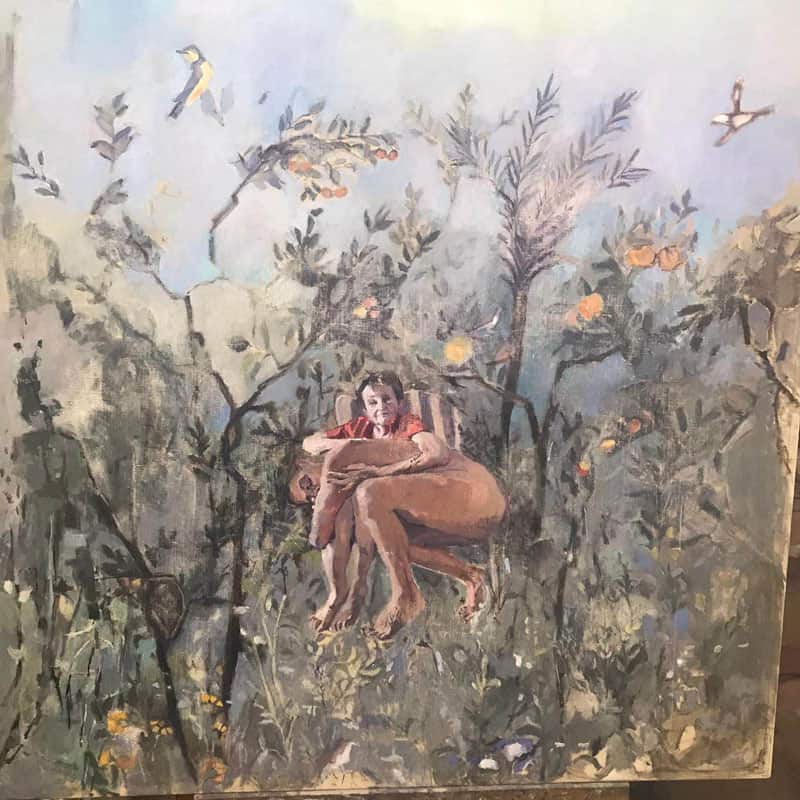

Eisenberg wrote about her experiences growing up during the first aliyah in an autobiographical Hebrew-language work, Among the Vineyards. (The character in her book modeled on herself is named Talia and her husband is named Ziv. )

“Talia grew up,” Eisenberg wrote, “amid vineyards and almond groves, between olive, sycamore, and carob trees, orange groves and eucalyptus woods, among Bedouin shepherds and farm laborers.”

From an early age, Talia was skilled in fieldwork, Eisenberg wrote, adding, “She was the best horseback rider in the village and could climb trees like a cat, swim faster in the water reservoirs than anyone else, milk cows, pick grapes, and ride a camel through the night to bring the grapes to the winery at Rishon Lezion. The other children in the village would gather to listen to her sing in the vineyard and beg her to dance the Bedouin sword dance around the fire.”

Love blossomed early in these wild Hebrew settlements, Eisenberg wrote: “On lovers’ hill, the youngsters of the village would meet in the evening, light a bonfire, sing, and talk of the future of Jewish settlement and Jewish labor,” among other topics.

Eisenberg met Harari at the age of 13, while he was a student at Mikveh Israel. The two fell in love and when Harari left for Switzerland, she waited for him for six years, communicating via passionate letters.

A year after Harari’s return, in 1907, they married. Eisenberg gave up her job as a teacher at the Evelina de Rothschild school for girls in Jerusalem and moved to Jaffa to join her husband. A year later, she gave birth to their first and only son, Yizhar (who would become an influential member of Knesset). For an independent woman – a horse and camel rider who danced around bonfires at night – becoming a housewife and a mother was not simple.

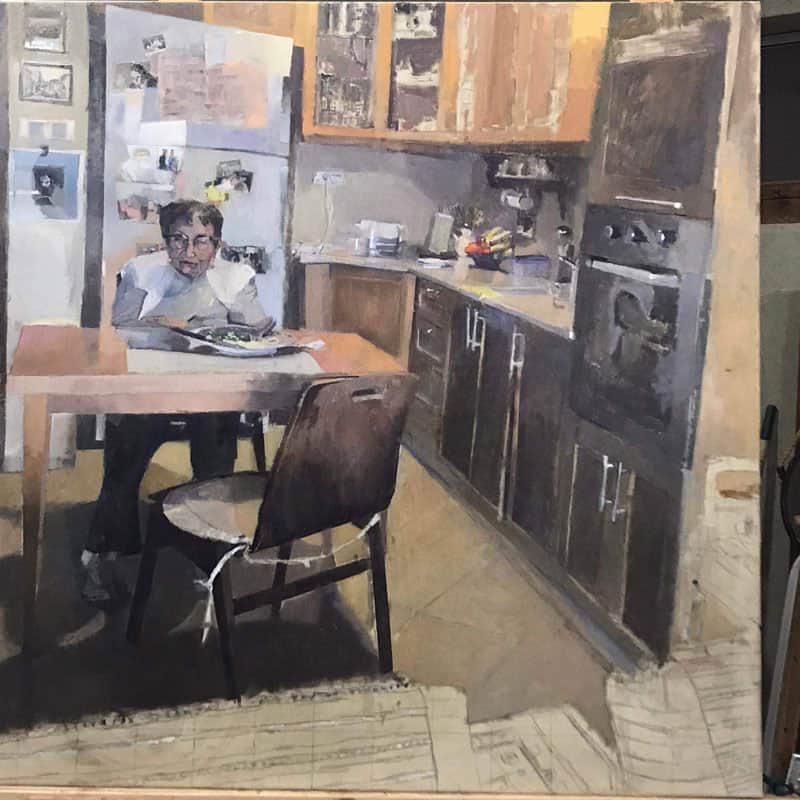

“The summer holidays are over,” she wrote of that first year in Jaffa, “the school has opened, and Ziv is busy day and night at the school, usually returning home after midnight. Talia awaits his return and suffers from loneliness. It is a pity that she left teaching, work that she loved so much, devoting her time to the house and kitchen. She dreams of returning to the school to teach, but all the positions are taken. She is dissatisfied with her life. Why does marriage have to change a woman’s life and imprison her at home? Why do men continue to live their former lives after marriage while a woman must give up all that is precious to her?”

When she became pregnant, Talia was scared she would lose the new job she had found in Jaffa and tried to hide her pregnancy as much as possible. Her husband tried to help her with the household chores, but was busy with his public work and not always available. She was filled with despair and feelings of abandonment. The birth was difficult – a forceps birth, followed by fear of blood poisoning. Her life in danger, the doctors decided to move her to the Shaare Zedek hospital in Jerusalem. While her husband was busy with his public activities, she was hospitalized far away, in Jerusalem, where she spent all her time “waiting for his visit.”

After she recovered, Talia returned to Jaffa to discover that the school had given her position to someone else.

“The gymnasium decided that it is better to hire a bachelor for the job instead of a married woman with a child. All Talia’s plans to continue working fell apart,” Eisenberg wrote.

The new mother did not despair. She began to give private lessons at home and filled her spare time by joining the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage, where she became one of the dominant figures in the group. Eventually, she would return to teaching at the school, but her love of Hebrew theater would accompany her for the rest of her life.

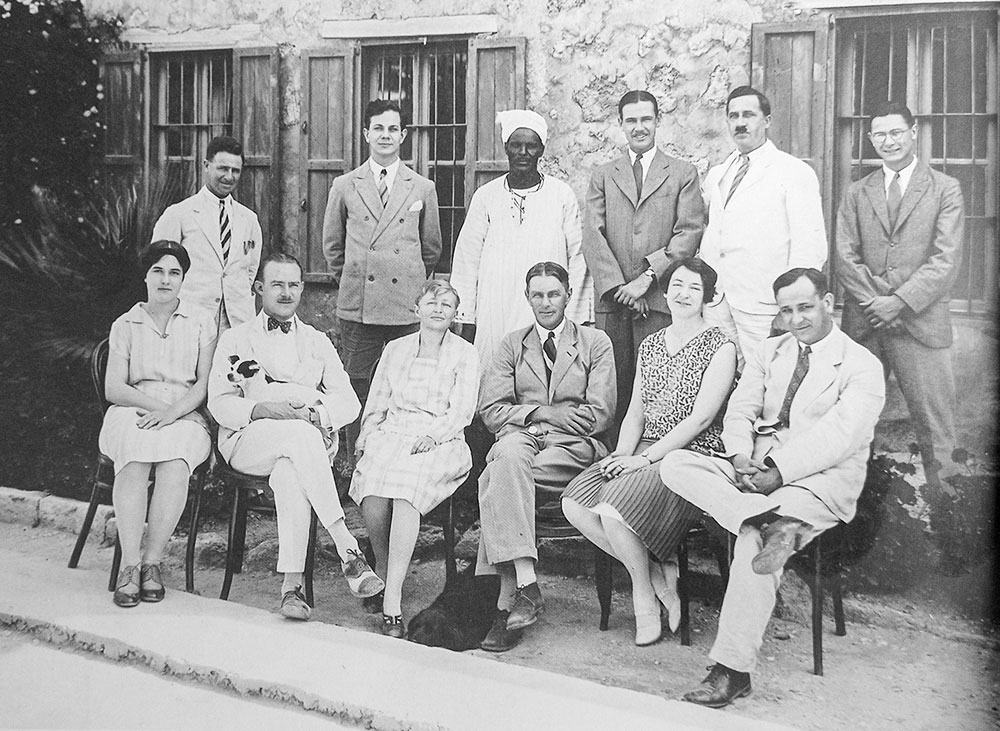

Above (left): Olga Hankin. (Tamar Eshel, from a family album)

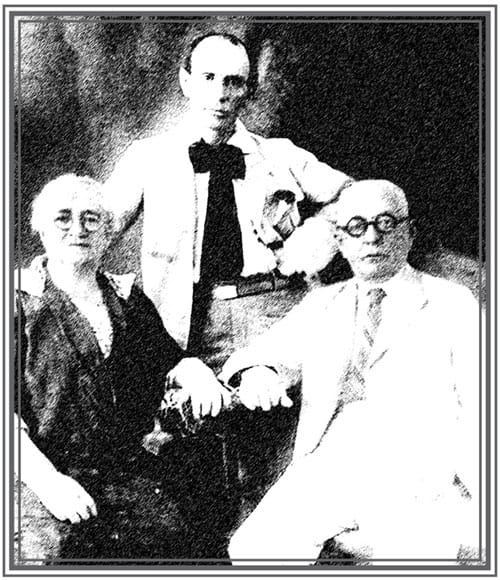

Gnessin, the third founder of the theater troupe, was a scion of a rabbinic family and the brother of writer Uri Nissan Gnessin. He made aliyah in 1903 from Russia, finding work as a simple laborer in the Rishon Lezion winery. Gnessin was fluent in Hebrew and Hebrew culture, loved art, had a rare talent for acting, and had a few years of experience on the stage.

The Lovers of the Hebrew Stage’s first production was Zerubbabel, which premiered in 1907 in Rehovot. News of the play set off a storm in the settlement. A rabbi from Jaffa insisted that neither women nor men dressed as women appear on stage. The group rejected the rabbi’s adjurations so he informed the Ottoman authorities that an indecent performance was in the works. On the opening night, Ottoman soldiers arrived at the community hall where the play was about to begin and prevented the curtain from rising.

The second play that the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage produced, Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, met the same fate. The rabbi informed the authorities and soldiers prevented the show from opening. However, the group would not give up. Eventually, the authorities disregarded the constant rabbinical warnings and the group began to perform its Hebrew plays in Jewish settlements, Jerusalem, and Jaffa.

In 1909, the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage welcomed its first Hebrew star: a young Sephardic woman from Alexandria named Lisa Varon. The new actress had appeared a few times with Yiddish theater troupes in Egypt. Even though she did not speak Hebrew, she was invited to join the group. Varon was a star from her very first performance; the audience loved her acting, her voice, and her beauty.

“The primitive actress who had never seen a real theater in her life, had no education, and did not speak Hebrew amazed us with her gentle, soft performance,” Gnessin wrote in his autobiography. “She was endowed with all the virtues of a great actress. She walked the stage like a princess, enthralling the audience with each dramatic gesture, with her beauty, her voice, her face. She was the first actress on the Hebrew stage who showed real acting skills.”

The Lovers of the Hebrew Stage was a success.

“Hebrew theater,” reported Ithamar Ben-Avi, the son of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (the father of Modern Hebrew), in Hazevi in 1910, “has arrived. We have some talents in the country. Harari, Shlomi, Hararit, Gnessin, Lina, and a few others always will be remembered as the founders of Hebrew theater.”

Despite his enthusiastic praise, Ben-Avi complained that theater remained an amateur affair, opining, “Why is there money for so many unimportant things and no money for Hebrew theater?”

Author Joseph Hayyim Brenner reported from backstage: “When the candles went out in the hall and only the tired actors remained, I found out that Gnessin and Varon are planning to leave the country. Why are they playing with us? We have finally created a Hebrew theater and now they are planning to leave.”

Brenner had predicted that this would happen. Varon’s success on the Hebrew stage went to her head and friends advised her to seek her fortune in the capitals of Europe. She left and was never heard of again.

On February 15, 1912, Ben Eliakim reported for Hazevi on another performance in Tel Aviv: “Tel Aviv is humming with people. In the light of kerosene lamps, people make their way to the theater in couples and groups. It is a festive day in Jaffa. They all are on their way to the theater – the women dressed in their best clothes, high heels tapping the floor, some speaking fluent Hebrew, some Russian, and others a jargon of Yiddish and Hebrew. Thirty minutes before the beginning, the hall is already full, sold out. A large crowd was left standing outside the ticket booth.

“There were about 1,000 people, a crowd never seen before for a Hebrew performance. The show started three-quarters of an hour late. As the third gong chimed, people were told to sit down, even those who wanted to watch the performance while standing.”

Ben Eliakim, the first Hebrew theater critic, had much to say about the performance.

“The acting is a little weak, Gnessin and Titleman are sorely missed … and all the actors in the last act did not fulfill their roles with skill,” he complained, noting one exception, the heroine of the play, Eisenberg, “was excellent.”

Despite the first Hebrew critic’s harsh criticism, he also noted, “The audience loved the play and clapped for a long time, leaving the hall fully satisfied long after midnight.”

The Lovers of the Hebrew Stage continued to perform until 1914, even after the loss of its stars. When World War I broke out, Jewish residents of Jaffa who were not Ottoman citizens were expelled from the city and the troupe disbanded.

Gnessin, who already had left the land by then, was involved in Nahum David Zemach’s attempt to create a Hebrew theater called Habimah in Poland in 1913. In 1917, he, Zemach, and Hannah Rovina tried to establish Habimah in Moscow. In 1923, Gnessin returned to Palestine and founded the Eretz Israel theater together with Shimon Finkel. When Habimah made aliyah in 1928, Gnessin joined what would become the national theater of Israel. In 1923, he acted in the first Hebrew movie, Oded Hanoded.

Eisenberg and Harari, the Metman-Cohens, and the Hankins were not only key members of the Lovers of the Hebrew Stage, but also were among the founding families of Ahuzat Bayit in 1909, the year before it changed its name to Tel Aviv.