Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav’s journey to the Land of Israel was much more than a dangerous trip to a remote part of the world. It was a rite of passage for the charismatic mystic who would admonish his followers to disregard all the teachings he made before the voyage

Dan Manor

During the eighteenth century, the belief that a voyage to the Holy Land has profound mystical implications motivated many Jews to undertake the dangerous journey to Ottoman Palestine. These attributes of the pilgrimage to the Holy Land, reinforced by actual immigration, played a significant role in the emergence of new ideas in the Jewish world, and especially in the development of the Hasidic Movement.

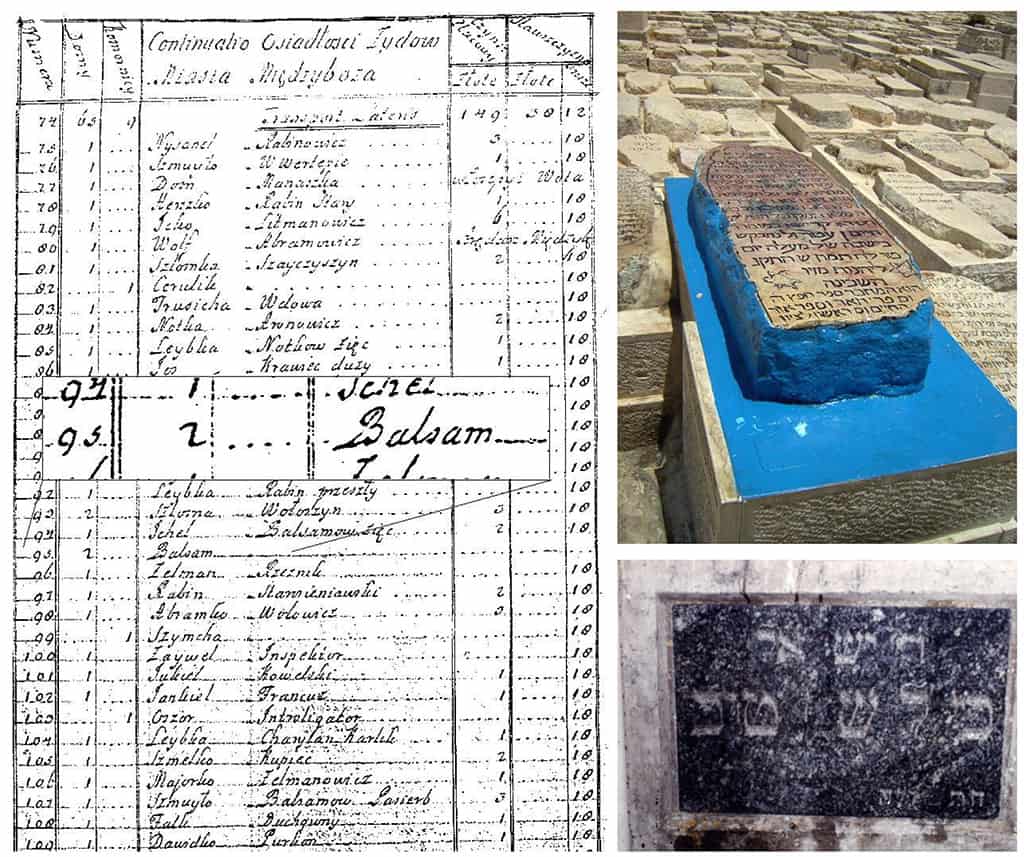

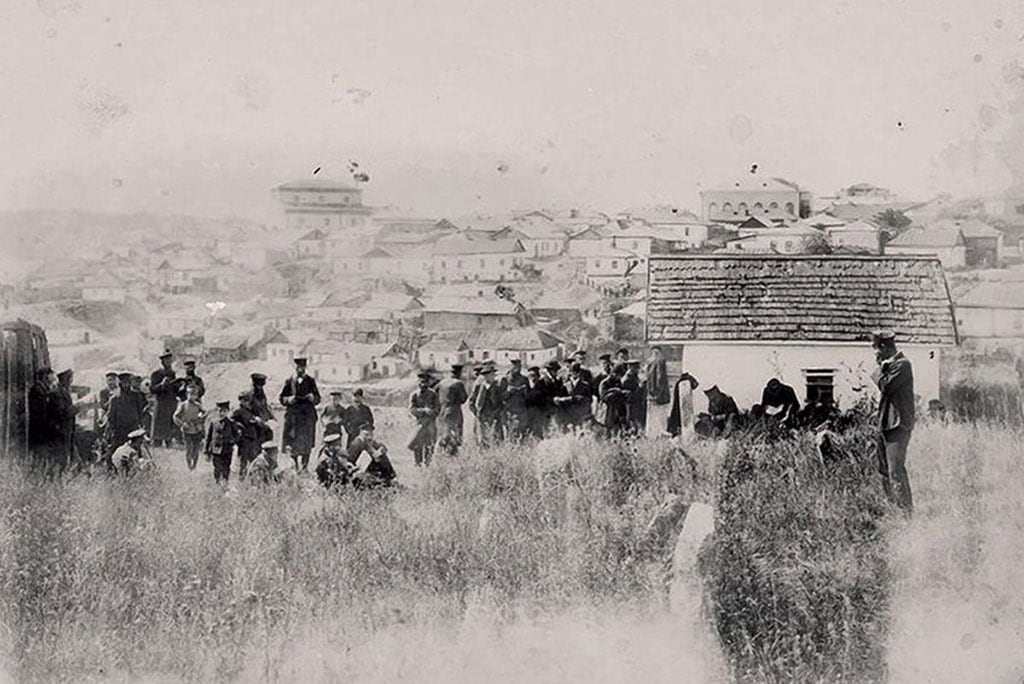

The cornerstone of the Hasidic engrossment in these voyages was the mysterious attempt of the Ba’al Shem Tov – Master of the Good Name – to travel to Eretz Yisrael in the 1740s. Israel ben Eliezer, the Ba’al Shem Tov, is traditionally accepted as the founder of the Hasidic Movement. However, his biography, as well as his trip to the Holy Land, is shrouded in legend. From Medziboz in Ukraine, the Besht, as the Ba’al Shem Tov is acronymically called, set out, with his daughter Adel and his attendant, Hirsh Sofer, to Istanbul, to take a ship to the Land of Israel.

The Besht arrived in Istanbul on Passover eve. However, when he planned to take a ship to Palestine, a mystical force held him back, warning him that he had to return to Ukraine for the good of his community. On the way back, this time by ship across the Black Sea, the vessel ran into stormy weather. Adel fell overboard; the Besht was imprisoned but managed to escape. These motives of storms, danger of enslavement, and evil forces that try to prevent the voyage all have mystical meanings that appear in many of the accounts of Hasidic journeys to the Land of Israel.

Objections for this deep spiritual ascending of the soul were considered meniyot – hindrances, sent by the forces of darkness

Even though the Besht failed to reach the Holy Land, he encouraged his relatives and close circle to settle in the Land of Israel. In 1747, probably a short time after the Besht’s attempt, his brother in law, Gershon of Kutov, led a small group of Hasidic families that settled in Hebron, and later Jerusalem. In 1764, Nahman of Horodenka, whose son married the Besht’s granddaughter, and Menahem Mendel of Premishlan settled in Safed, and later Tiberias. Thirteen years later, Menahem Mendel of Vitebsk and Abraham of Kalisk led the first Hasidic Aliyah, over 300 people, who settled in Safed, Tiberias, and Pekein in Upper Galilee.

The Ascent of the Tzadik

Half a century after the voyage of the Besht, his great-grandson, Nahman ben Simhah, known as Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav, decided to set out for the Holy Land. At the age of 26, he already had eight children and a small circle of followers.

On the eve of Passover 1798, the 26-year-old Nahman ben Simhah announced his plans to depart for Eretz Israel. The declared purpose of the journey was to commune with his grandfather, Nahman of Horodenka, buried in the cemetery of Tiberias.

Objections for this deep spiritual ascending of the soul were considered meniyot – hindrances, sent by the forces of darkness to prevent Nahman from fulfilling the spiritual mission that would hasten the days of redemption.

“As long as I breathe I will deliver my soul and ascend to the Land of Israel,” he explained to his protesting wife: “You can find work as a cook, the older girls as household servants and their younger sister can be taken into someone’s house out of pity. I shall sell everything in the house to cover expenses for the journey.”

The account of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav’s journey to the Land of Israel was recorded by his closest follower Nathan Nemirov, after Rabbi Nahman’s death, and is based on recollections shared with Nathan by Simeon, Rabbi Nahman’s companion on the trip.

Rabbi Nahman later explained that this was an essential part of the journey, part of the necessary descent of the Tzadik, to prepare for the ascent to the Holy Land

Rabbi Nahman’s announcement of his decision to travel was preceded by a mysterious journey, to the town Kamenets-Podolsk, known as a center of the much-hated Frankist Movement, an extreme Shabbatean offspring. As no Frankists still lived in the town, it seems that the visit had mystical connotations of purifying the souls of the long-gone Frankists. The idea of the Rebbe, the Tzadik, as a redeemer of souls is purely Sabbatean; an ascend to the most sacred levels must start with a descend to purify the most defiled of human space.

A month after his announcement, on May 4, 1798, Rabbi Nahman and Simeon set out from Medevedka, Ukraine. They traveled overland to Nikolayev 270 kilometers to the south and found passage on a barge carrying wheat down the Dnieper River to Odessa. From Odessa they took a ship to Istanbul on a stormy four-day voyage.

While waiting for the steamship to Jaffa, Rabbi Nahman started behaving strangely. “He went about barefoot, without a belt, and without a top hat. He would go about in his indoor clothing, running around the market like a child. There he would play war games, as children do.”

Rabbi Nahman later explained that this was an essential part of the journey, part of the necessary descent of the Tzadik, to prepare for the ascent to the Holy Land. When a group of Hassidim from Ukraine arrived in the city, led by Rabbi Zeev Wolf of Charny-Ostrog, a disciple of the Maggid of Miedzyrzec, Nahman warned his disciple not to reveal his identity to them.

A Stormy Arrival

In May 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte set sail from Toulouse to conquer the East and sever England’s hold on India. A large French fleet, carrying an invasion force of 35,000 soldiers, made its way across the Mediterranean to Alexandria, trying to dodge the English navy under the command of Horatio Nelson. As the battle in the Eastern Mediterranean raged, the Jewish community in Istanbul announced a ban on journeys to the land of Israel.

“Our master did not pay any attention to this,” writes Nemirov, “he wanted to risk his life. He said to the one who accompanied him: know that I want to place myself in danger, even great and terrible danger. However, I do not want to risk your life. Therefore, if you want, take money for expenses and return home in peace. I shall travel on alone, unbeknown to the people of Istanbul. For I risk my life come what may.” Simeon declined and stayed on.

Following the request of a well respected Sephardic sage from Jerusalem, the Istanbul Jewish community permitted one last ship to sail for Jaffa, taking Rabbi Nahman and Simeon to the Holy Land. As they approached Jaffa, the ship ran into a storm.

Making their way to the harbor, the two Hasids who spoke no Arabic or Turkish tried to find their ship. By mistake, they boarded a Turkish battleship

“Everyone cried out to God… but our master sat in silence… when the wife of the Rabbi of Khotin, a learned woman, who had been chanting and praying all night asked him why he was silent, he said: by this, you will be tested. If you are still, the waters of the sea will become still as well.” The passengers followed his counsel, the storm abated, and a fortuitous wind blew them into the port of Jaffa. Rabbi Nahman, in his strange clothes, was not allowed to disembark. The port officials were suspicious that he might be a French spy and refused to let him off the ship. He remained on board proceeding northward and disembarked at Haifa on Monday, September 10, 1798 – the eve of Rosh Hashana.

When the Hasids in Tiberias learned that the great-grandson of the Besht was in Haifa, they petitioned him to come to Tiberias and pray with the community during the High Holidays. Nahman refused. He wanted to spend the holy days of the beginning of the year by himself in contemplation.

After the festive Rosh Hashana dinner, Nahman sunk into a deep depression and announced his wish to depart immediately from Eretz Israel. During this time of deep melancholy, a strange incident developed. An Arab in Haifa took a liking to Rabbi Nahman and began visiting him regularly at his quarters. Failing to gain Rabbi Nahman’s affection, he challenged him to a duel. Rabbi Nahman and Simeon hid in the home of the Rabbi of Charny-Ostrog, who had arrived in Haifa with them. The Arab was appeased, and Rabbi Nahman began to feel better. After a month in Haifa, he left for Tiberias, where he was joyously received.

Rabbi Nahman spent the winter in Tiberias, studying Kabbalah and praying on the grave of his grandfather, and the graves of Rabbi Shimeon Bar Yohai in Meiron, Rabbi Ashkenazi Luria in Safed, and other sages in Galilee. The news that the great-grandson of the Besht was in the land soon spread to the Four Holy Cities and Hasids from around the country flocked to hear him teach.

Acre Under Siege

Napoleon’s forces arrived in Galilee in March 1799. After capturing Jaffa, at the beginning of March, Napoleon advanced along the coast, reaching Haifa ten days later. Rabbi Nahman understood that it would soon be impossible to leave, and he and Simeon headed for Acre, arriving in the city on Friday, March 15, three days before the first French troops appeared before the walls. He hoped to find a ship flying the flag of neutral Ragusa. In Acre, pandemonium ruled. The news of Napoleon’s massacre of the population of Jaffa, coupled with the announcement of the Turkish governor of Acre, Jazzar Pasha, that all civilians should leave the town by Sunday, resulted in a rush for the harbor. In the last possible moment, on Sunday, March 17, Rabbi Nahman and Simeon managed to book passage on a Turkish merchant vessel.

Making their way to the harbor, the two Hasids who spoke no Arabic or Turkish tried to find their ship. By mistake, they boarded a Turkish battleship, that as soon as it left the harbor, was engaged by a French warship. Rabbi Nahman and Simeon, on a ship embroiled in a raging battle, hid in a small cabin afraid to be discovered by the Turkish sailors and thrown into the sea. Their only help was the ship’s cook, who took pity on them and brought them coffee and biscuits twice a day.

Once away from the shore and out of range of the French warships, they ran into a storm. The ship began taking on water, and all excess cargo was thrown overboard. The small cabin where the two stowaways were hiding began to fill with water. To escape drowning, they climbed on top of a large cabinet and prayed in terror as the sailors fought to get control of the ship.

After four weeks at sea, on the eve of Passover, the ship sailed into the harbor of Rhodes. Rabbi Nahman and Simeon, now in the hands of the ship’s captain, were ransomed from slavery by the Jewish community. The ship’s captain, they found out, had a reputation of enslaving and murdering captives he could not sell.

The rabbis of Rhodes were honored to have the Besht’s descendant among them. After spending Passover in Rhodes, they were put on a fast vessel that took them to Istanbul in three days. In Istanbul, it turned out that their papers were not in order, and they had to bribe the officials to let them continue on their way. They took a ship to Galati, ran into a storm during which most of the passengers drowned. They arrived home after traveling overland from Galati via Jassy sometime in early summer, 1799.

Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav’s voyage was a rite of passage. A dangerous journey that would reveal hidden secrets and insights reserved for the true Tzadik. The trip was a turning point in his life. It was only after his return, at the age of 27, that he agreed to become a public figure proclaiming that any teachings of his before the voyage should be deleted and forgotten. “Where ever I go, I am going to Eretz Israel” became one of his most famous sayings.

Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav’s voyage was a rite of passage. A dangerous journey that would reveal hidden secrets and insights reserved for the true Tzadik

Nathan Nemirov, in his account of the trip, details his Rabbi’s reasons for making the voyage; “The hope of receiving some revealed knowledge at the grave of his grandfather – and also some higher form of insight and illumination that can be had only through a journey to the Holy Land.” The dangers encountered along the way gave the voyage a higher spiritual meaning.

In 1802 at the age of 30, Rabbi Nahman settled in Bratslav, where he spent most of the remaining eight years of his life. In 1810, stricken with tuberculosis and ailing, he journeyed to Uman, where he had chosen to be buried. Despite his illness, he celebrated Rosh Hashanah with several hundred followers. During the first day of the festival, his situation deteriorated seriously, and he coughed large quantities of blood. Nevertheless, despite his great weakness, he gave his traditional teaching on the second evening, speaking for many hours. It was to be his last lesson. Eighteen days later, on October 16, 1810 – the fourth day of the festival of Succot – Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav passed away. He was buried in the old cemetery of Uman.

On the last Rosh Hashana of his life, Rabbi Nachman stressed to his followers the importance of being with him for that holiday in particular. After his death, an annual Rosh Hashana pilgrimage to the Rabbi’s gravesite was initiated. Until 1917, the pilgrimage, called the Rosh Hashana Kibbutz, drew thousands of Hasidim from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and even Poland. Following the Russian Revolution, the pilgrimage was outlawed, and only a few followers managed to clandestinely get to the grave on Rosh Hashana. Following the 1989 fall of the Soviet Union, the gates were reopened, and since then, over thirty thousand Hasids attend the Rosh Hashana Kibbutz every year.

This year, due to Covid-19, authorities in the Ukraine and Israel prohibited the gathering. The Hasids waited for a miracle. Still, none appeared to prevent what Rabbi Nahman would have considered a miniya.