From the orchards of Hadera to Judaica in Naharia: artist Adina Gatt celebrates her eightieth birthday in these unusual times

Arbel Weinberg, Photos courtesy of Adina Gatt

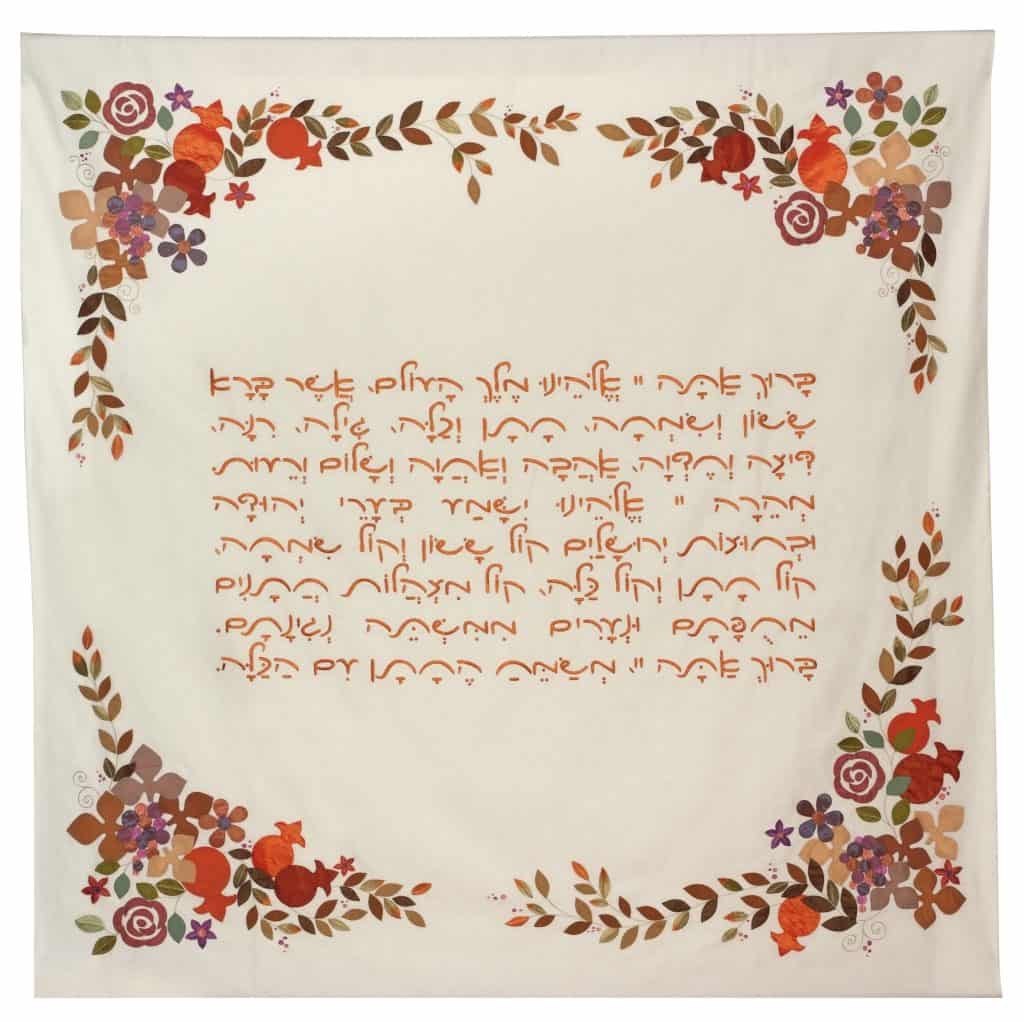

You may have come across some of Adina Gatt’s unique work in your everyday Jewish life; at the “Young Israel” synagogue in century city, Los Angeles; in the “Adat Israel” synagogue in D.C., in the “Yamin Moshe” temple in Jerusalem, or the “Hovevei Tzion” synagogue, in Chicago. Perhaps you were married under one of her exquisite chuppas or prayed with an embroidered tallit. Now, nearing eighty, Adina Gatt decided to wrap up her life’s work, and close the Ephod Art Embroidery studio in Naharia, Israel.

Saying goodby to thirty-eight years of a labor of love is not easy. The current COVID-19 crisis makes it even harder. But in the Ephod studio in Naharia, it seems that Gatt is more concerned with finding the right color combination for a commissioned Torah mantle than pandemics.

“It started after my father, Abraham Replanski, passed away,” she tells us. “I was already in the textile art business with my partner, Yael Shilo, but we were not creating Judaica. My mother wanted to commemorate my father by donating a new parochet – the curtain that covers the Torah Ark, to his synagogue. She was planning on ordering one from Bnei Bark. I asked her to let me make it in his honor. He was a wonderful father, an entrepreneur, a bit naïve, but a man of great compassion. My mother was surprised but happy. We embroidered the verse “Sing the Lord a new song,” from the book of Psalms on the curtain. I felt as if I was giving birth to something new. Later, my mother told me that she had gone ahead and ordered the one from Bnei Brak. She wasn’t sure we would make it on time.”

An Israeli Tapestry

Gatt was born in September 1940, in a tiny house in Hadera –at the time a small farming town, surrounded by citrus orchards. She had two older brothers and one younger one. Her parents – Fania and Abraham, had made Aliya in the early 1930s. The Replansky home was soaked with tradition and religion, intertwined with Zionism and influenced by the landscapes of a new homeland and the many different people around them. Abraham’s father, who lived with the family, was a Slonim Hassid. Synagogue liturgy and biblical verse, along with the pioneering agricultural spirit, created a new multicolored Israel tapestry. When she was almost 13, Gatt was sent to study at the Nahalal Agricultural School. At the age of 18, she joined a new semi-military Nahal agricultural settlement, and from there to Kibbutz Revivim in the Negev. It was a pioneering lifestyle, far from being religious or artistic. But the seeds sown in the fertile groves of Hadera bloomed in Revivim. “When you entered my home in the kibbutz, the first thing you saw was a portrait of Ben Gurion,” Gatt tells us. “His words, ‘Golden youth go to the Negev,’ were for us the eleventh commandment.”

Adina married Alon Gatt (Weinberg) and had a boy and a girl – Carmel And Sharon – and then said goodby to the Kibbutz. “When Carmel was born, I put him in the Kibbutz children’s home. That was the norm. For me, it was a terrible year. After Sharon, I knew I could not do it again.” So the young family left the Negev and settled in Naharia, in Western Galilee, a peaceful resort town on the Mediterranean, not too far from the Lebanese border. “My father had worked in construction in the area and was familiar with the town. He bought a plot of land in one of the outlying neighborhoods, surrounded by agricultural fields and open spaces. Buying real estate was very cheap back then.”

Her two other children, Yarden and Hadar, were born in Naharia, and that is where she met the artist Yael Shilo, who introduced her to the world of textile art. “I used to host art exhibitions at our home,” she muses. “Naharia had no art gallery, and I brought artists like Inus, Nahum Guttman, Ester Peretz Arad, Mario Doretti, and others to exhibit in our house. Yael Shilo came to one of the exhibitions and asked me if I would arrange an exhibition for her. I saw her work, loved it, and we joined forces.” They worked together for two years before they created their first parochet. During those two years, Gatt and Alon parted ways. Shilo created intricate wall hangings, and the two branched out to other fields. “We created embroidered fashion; vests, shirts, and espadrilles. But the way that the first parochet was received made us concentrate our efforts on Judaica. For me, it was a calling.”

A new Song

Ceremonial art was one of the first forms of art in Judaism. The bible dedicates seven chapters to the divine manual on how to build the tabernacle; structures, materials, tools, decorations. God even handpicked the artist to make it; “Then the Lord said to Moses, see, I have chosen Bezalel, son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah. I have filled him with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills to make artistic designs in gold, silver, and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood, and to engage in all kinds of crafts” (Exodus 31). In the early days of Jewish resettlement in the land of Israel, the founding artists of the Bezalel Art Academy in Jerusalem immersed themselves in traditional Jewish art, adapting it to represent modern art forms. “But,” says Gatt, “When we founded our textile studio, Ephod, textile Judaica was not part of this new modern art movement. The novelty represented by metal, wood, and stone was not applied to textiles. Most of the textile artifacts were clichés, blue velvets, gold lions, tablets of the law, and a few biblical verses that had been used for decades. For me, the connection to Judaism was personal, a place where each person can find the one verse that has a special personal meaning. As a Judaica entrepreneur, my own special biblical verse was the instructions given in Exodus 28:15, for making the high Priest’s breastpiece: “Fashion a breastpiece for making decisions – the work of skilled hands. Make it like the Ephod: of gold, and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and of finely twisted linen.”

Word of the unique Jewish art being created in the studio in Naharia spread to Jewish communities around the world. Soon, Gatt found herself flying to Canada and the United States, sending art from the studio to Vienna and Australia, Sao Paulo, and more. “The world is small, the Jewish world – even smaller. One client led to another, each congregation to a new community.

When Shilo left Ephod, Gatt moved the studio to her home, but it remained a hive of activity with women from around Israel taking part in the work; stitching, embroidering, ironing, and drawing. “It is very emotional creating these unique pieces, each one dedicated to a single person. To formulate the design, I search the bible to find the exact fitting verse.” One such piece, a chuppah, created not long ago, was made in honor of Ori Ansbacher, a 19-year-old girl who was murdered in Jerusalem. The brutality of the murder and the radiant personality of Ori resonated throughout the country. “Rabbi Bat-Sheva Sadan called for women around the world to embroider a square in Ori’s memory. We received around 5,000 embroidered squares, in a myriad of materials and colors, each one telling a unique story. We chose 144 of the squares and sewed them together to create a beautiful huppah embroidered with a verse from the book of Isiah: ‘Arise and shine (Ori), your light has come,’ with a poem Ori wrote embroidered on the rim.”

Ephod’s creations are an integral part of many family and community events, sad and joyous. “A huppah I made for a certain family, a long time ago, has already seen three generations of children married under it. For each wedding, the names of the newlyweds are added on the fringes.”

As she approaches eighty, Gatt is planning to close the studio. However, her work is here to stay with a new song every day.