Fifty years have passed since the end of the War of Attrition, and the Israeli media and public are still not ready to acknowledge the trauma of that forgotten war.

Together with most of my friends the IDF called us up to enlist in November 1967, one of the first group of conscripts right after the Six Day War. It was a euphoric time replacing the tension that had prevailed in Israel for months. The photograph of the weeping Israeli soldier at the Western Wall graced the world media together with the famous image on the cover of Life magazine showing a young Israeli armored brigade officer, cooling off in the waters of the Suez Canal.

The pastoral atmosphere lasted for less than three weeks. On July 16, 1967, Egypt launched a massive shelling along the entire length of the canal as well as a commando raid on the eastern bank. Eight IDF soldiers were killed, 40 were wounded, and two were captured. Exchanges of fire became part of the daily routine along the Suez Canal. On September 8, 1967, a massive Egyptian artillery assault killed 10 IDF soldiers and wounded dozens. On October 21, 1967, Egyptian forces sunk the Israeli destroyer Eilat. The IDF responded by leveling the refineries in the city of Suez. The Egyptians retaliated by shelling the entire length of the canal again plus a commando raid that claimed the lives of 15 IDF soldiers. On October 31, 1967, IDF paratroopers hit three sites deep inside Egypt, bringing calm to the Suez Canal for a short time.

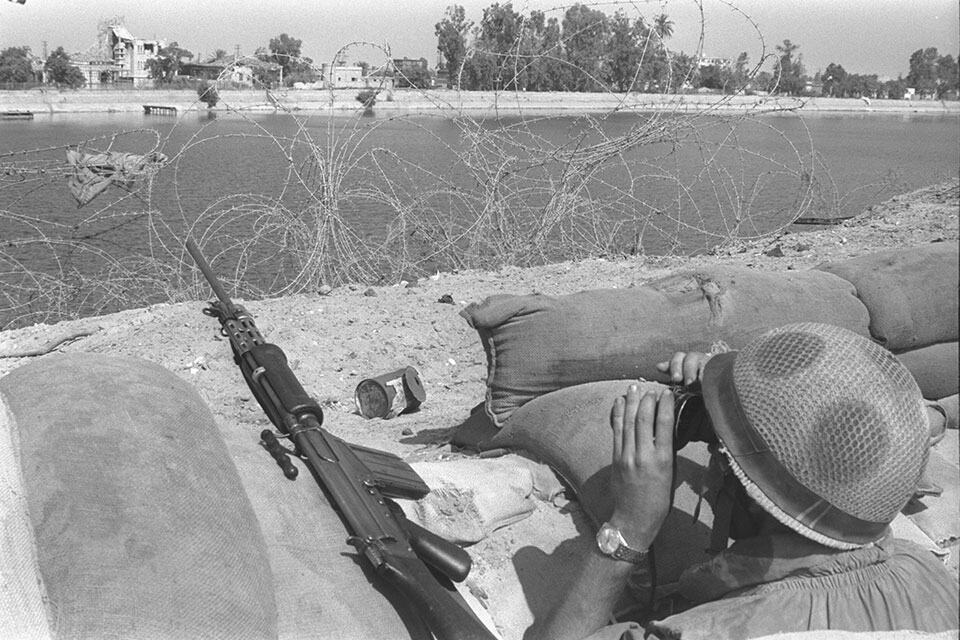

The artillery assaults on the Egyptian front made it clear that the IDF needed to find a way to protect its forces there. After a stormy debate IDF Chief of General Staff Lt.-Gen. Haim Bar-Lev decided to establish a series of forts along the entire length of the 160-kilometer Suez Canal. They would be strategic lookout posts that could alert Israel to Egyptian movements as well as provide soldiers with the best protection against shelling and snipers. The Egyptians dubbed the 32 outposts that Israel constructed between Port Said and Suez the Bar-Lev Line.

My newly recruited company was sent to the canal to help construct the Bar Lev line, setting up camp on the canal near the Mitla Junction. Our company of new recruits settled into pup tents in a small, sandy valley some 100 meters east of the canal, where construction of the outpost was commencing. Along the Suez Canal, the winter of 1967 was characterized by clear daytime skies, blazing afternoon sun, and chilly evenings illuminated solely by the moon and stars. There were no electrical lights in the vicinity. The electric grid on the western bank had been destroyed in the war. We, on the eastern side, had no desire to become targets so maintained a complete blackout at night. The dunes gleaming in the moonlight was an amazing vision for us, young soldiers pitching tents in a real desert for the first time. One night, while I was on guard duty, as I patrolled the area around the tents, I saw a beautiful fennec (desert fox) in the moonlight. It stood atop the dune above the tents, straightened its large ears, and gazed in amazement at the humans burrowing into the sands that were its home.

After an almost enchanted month at the Suez Canal, we returned to our base to finish basic training. I then proceeded to a squad commander course followed by an officer’s course at military training camp 1, which had just relocated to Mitzpe Ramon, the local Israeli desert.

The pastoral winter of 1967 came to an abrupt end. Egypt claimed that erecting a line of fortifications along the canal violated the ceasefire agreement and on March 8, 1969, while the efforts to build the Bar-Lev Line were at their peak, launched an artillery attack along the entire length of the canal. On March 9, the Israeli counterattack claimed the life of the Egyptian chief of staff, Abdul Munim Riad, and other senior officers that were visiting the headquarters on the front line of the canal. The construction of the Bar-Lev Line was completed under fire, requiring additional reinforcement of the outposts.

“We have begun the second stage of pushing Israel out of Sinai,” Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser announced. “The first stage, rebuilding the army, has been completed. The second stage is harb al-astnazaf.” The literal translation of harb al-astnazaf is a blood-letting war, yet Nasser’s words were toned down in translation to “war of attrition.” In any case, in June and July 1969, this war claimed the lives of 75 IDF soldiers and wounded dozens of others. The fighting at the canal took a final toll of 367 killed and 999 wounded on the Israeli side. By the ceasefire in 1970, the number of Israelis killed on all fronts totaled 968 and the number of wounded came to 3,730. It is estimated that some 10,000 Arabs lost their lives in the War of Attrition.